Do I snap photos of every individual flower of the altar decoration with a macro lens and ring flash two minutes before the start of the divine service? Should I hide four radio-controlled flash units in the floral arrangements to create better lighting for the altar space? – What works and what doesn’t?

What might I do as a photographer to draw the wrath and condemnation of others? How might I annoy the members and ministers by disturbing their sanctification and worship? Or better yet, how do I manage to ensure that all are generally content and that I still have some good photos to complement the written report of the event?

Sanctification and worship

“In the divine service the congregation gathers to hear God’s word and receive blessing through the sacrament. Human beings worship God in reverence and humbleness. Thus divine service is an encounter between God and man. In the worshipful serving of the believers and in the perceptible presence of the triune God, the congregation experiences that God serves them in love.” So runs the description in the Catechism of the New Apostolic Church (CNAC 12.1.1).

Photographers are not mentioned in this little excerpt. And this perhaps explains the malaise that arises here and there when the foreign body known as “person with camera” pops up. After all, for those participating in the divine service (and for photographers too, as a rule) it is important to ensure that this place—which is set apart from all others—is the one place where a special measure of sanctification and worship is possible.

The clicking sounds of a reflex camera are just as unsuited to this as a photographer creeping through the aisles at an inappropriate moment. One’s personal thoughts and feelings are quickly disrupted if unwritten rules are not given the necessary attention.

Too innovative?

- Snapping a great shot of the members while they are praying—after all, they have finally stopped moving and are not putting up any resistance!

- Using the camera’s preview function during the divine service to show the person beside you in the bench the best snapshots you have taken so far.

- Calling out, “Move aside!” and loudly making room to take one last photo before everyone leaves—only after you have been chatting with an old friend for the last fifteen minutes.

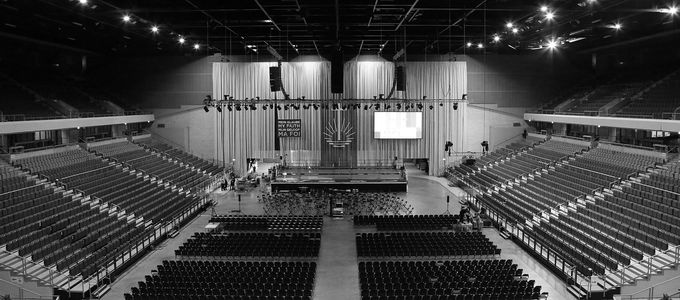

- Being convinced, even after your third failure, that a small compact camera is quite sufficient for photography in large halls, and that anything more merely represents disproportionate, commercial, and technological delusions on the part of a few individual freaks.

- Running around behind the second photographer and attempting to snap a second shot of as many of his photos as possible. After all, in your photography workshop, you were taught to learn from other photographers!

- Quickly powdering the face of the officiant while the choir sings so that the light reflecting from his sweating brow is not so strong.

- Loading up empty rechargeable batteries on the audio-video system during the service. After all, here there is free electricity and the Deacon would have nothing to do otherwise.

- Publishing photos even when the persons depicted in them have expressly told you not to do so. After all, they are brothers and sisters in faith, and most likely did not mean it like that.

Exaggerated? Unrealistic? — By no means! All of these things have indeed happened somewhere at some time before.

“Whatever you do, take lots of great photos!”

A photographer has quite a balancing act to perform: correctly and accurately adjusting the focal length, aperture, exposure time, and ISO value for every single photo, and still managing to be at the right place at the right time. Not to mention, he is to be as unobtrusive and noiseless as possible—if anything he might be recognisable for a fraction of a second, and even then he had better not run into the view of the video camera.

The media age requires photos—including pictures of divine services, devotionals, and concerts. Thousands of websites of the New Apostolic Church depend on meaningful, descriptive texts and splendid photos. It is part of our public relations work to bring something of our experiences of faith, and the special events of our faith, to the attention of our neighbour.

What is helpful?

A talk ahead of time with officiants, ushers, and editors about the scope of photography required for a particular event makes the work more tangible, and helps clear up possible misunderstandings. Wherever possible, it is better to take photos when there is some light “background noise” (that is, while the choir or congregation is singing than in the brief pauses between hymns, or during the sermon, rather than in the brief pauses in speaking). If available, use silent mode and avoid shutter sounds by using the appropriate camera setting. Deactivate any beeping noises—after all, the camera can also tell you in the viewfinder when the focus is right. Do not take photos during collective or personal prayer. Plan short routes and do not run around when it is not necessary.

You can learn other tips in casual conversation with other photographers. And beyond that, the feedback of officiants—whether requested or not—can also be of help.

And no: by no means should you ever hide four radio-controlled flash units in the floral decorations. And a macro lens is not necessarily a must in a photographer’s basic equipment for a divine service.