The year 2017 marked an anniversary year. Exactly one hundred years before, the New Apostolic Church had started to officially celebrate Holy Communion without sharing the cup. Here is a brief recap of our wafer history.

Not only was it almost impossible to find wine for Holy Communion during World War One, but there was also a fear of epidemics. The most hygienic and economical solution was wafers sprinkled with drops of wine. Such wafers were already being sent by military mail to soldiers fighting at the front. This was introduced on Good Friday 1917 by Chief Apostle Hermann Niehaus.

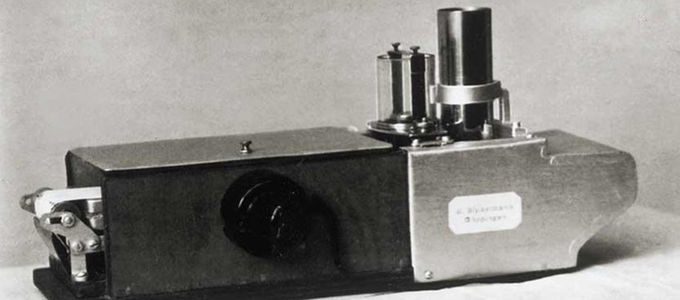

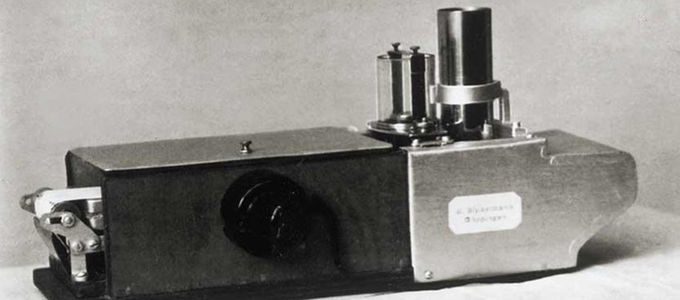

Finding suppliers for wafers was not the problem. The challenge was to apply the three drops of wine to a sufficient quantity of wafers. At first, this was done by hand—either with eyedroppers, syringes, or cork stamps and wooden sticks. But there was help on its way: a church member constructed a stippler, a kind of stamping device.

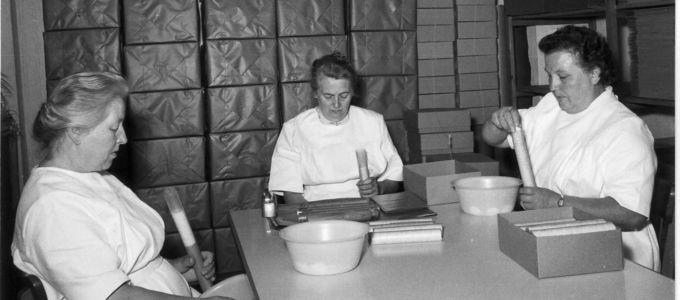

From handmade applicators to fully automated facilities

Things started to become more professional when Max Pflug, a master baker and a Priest in the congregation in Herne (Germany), started with the production of communion wafers. In 1931 the Church took over the operation of the bakery. It built new facilities in Bielefeld.

Production increased with the growth of the Church: from a yearly production of 9.7 million at the beginning to 238 million in the year 2001. In order to produce economically for the largest customers, other Church-run communion bakeries were established in Cape Town (South Africa) and in 2012 in Lusaka (Zambia).

Bread and wine, a question of form

Different churches have different ways of celebrating Holy Communion—traditions that are a thousand years old. The Catholic Church, for example, uses bread without any rising agent. The Orthodox Church, on the other hand, insists on using rising agent (leaven). Externally, the bread went from a thin flatbread to a small round wafer.

While the Eastern Church insists on red wine, the Western Church also allows white wine for practical purposes. The Methodists, for example, and United and Reformed Churches prefer grape juice. In the Catholic Church it is traditionally the priest who drinks from the cup, while in the Protestant Church priests share the wine with all communicants.

The importance of the sacrament

The positions were not only different in terms of form, but also in terms of content. Some Reformed Churches, such as the Mennonites, Baptists, and the Pentecostal Church, and many evangelical churches share the view that bread and wine are only symbols of Christ’s presence. The Roman Catholic Church, the Lutheran, the Orthodox, and the New Apostolic Church, on the other hand, believe in the presence of Christ in Holy Communion, the so-called real presence.

At the beginning of the 1920s, the New Apostolic Church saw Holy Communion merely as the confirmation of having received forgiveness of sins. The relationship between the forgiveness of sins and Holy Communion changed dramatically within a period of seventy years: Holy Communion today is the central event of divine service, the forgiveness of sins the prerequisite for its worthy reception.

An image of Jesus Christ

Not only the wafer, but also the communion vessels began to change over time. After decades of diversity, a trend towards uniformity began to be seen starting in the 1950s. A communion cup that was bulbous in shape began to emerge. In a pragmatic way, this vessel combined the various traditions: the paten (the shallow dish) migrated into the cup as an insert. The arched metal lid distinguishes the vessel as a ciborium. The biggest embellishment was the cross on it.

There is only one question that remains: the position of the three drops of wine on the wafer. Originally, an image of the crucified Christ was imprinted on the wafers. And the drops of wine were applied exactly there where the arms and legs of Jesus were attached to the cross. In 1990 this imprint was changed to the symbols Alpha and Omega. According to Revelation 22: 13 they represent the exalted Christ: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End, the First and the Last.”