Successful recipes are a trade secret—normally. But this is not the case when it comes to the products of the New Apostolic wafer bakery, which are distributed around the world by the billions. Here is a look behind the scenes.

Starting in 1917, hygienic concerns and economic hardship made it necessary to replace the wine chalice being used in the celebration of Holy Communion in the congregations of the New Apostolic Church around the world. At first, it was difficult to find a way to apply the wine to the wafer in little drops. The sprinkling apparatuses and waffle irons of the early years eventually developed into the production lines we know today.

From flour to the wine-sprinkled wafer

Forty-nine litres of water and 39 kilograms of Type 405 flour: so reads the basic recipe of the wafer bakery in Bielefeld, Germany—the oldest and largest production facility of the New Apostolic Church. The only other thing that is put into the mixing machine is a little lecithin to make the automatic process run smoothly.

Every 45 minutes, an employee mixes new dough and adds a few more litres of water as needed, depending on the consistency of a given load of flour. The dough then flows through some pipes from the adjacent room over to the baking machine, which dominates the actual production room.

The large machine has 31 “waffle irons”, into which the dough now flows. Each sheet then runs through the oven for about one minute before the oven opens again and a burst of air pushes the baked sheet, which weighs less than 20 grams, onto the conveyor belt.

When they are fresh out of the oven, the baked sheets are quite dry and brittle. This means that further processing would cause some crumbling. The sheets are therefore sent to the conditioner. After being exposed to steam for five minutes, the wafer sheets are flexible enough to continue their journey undamaged.

So far, so good. It is only in the sprinkler that the wafers receive their special New Apostolic character, namely three drops of wine made from a grape variety known for its dark colour. Each wafer receives about one square millimetre of thickened wine, which is boiled for twelve hours and thus loses most of its alcohol content.

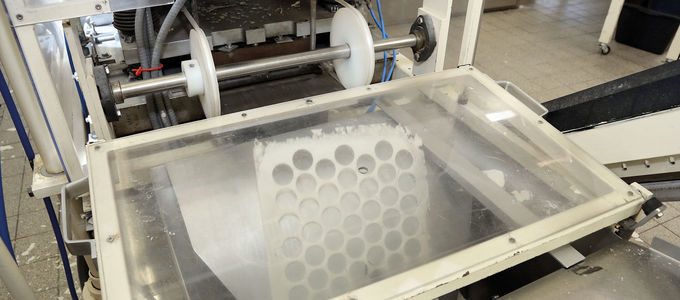

The second-last stop in the production process serves to stamp out the wafers: each baking sheet yields 73 round wafers. The remaining dough around the wafers is shredded and disposed of in an environmentally friendly way—in either a composting facility or a bio-gas plant.

Now the wafers make their way to the packing station: some 1,600 wafers are deposited into a standard-sized box. And since the wafers are not counted, but rather weighed, there are sometimes more and sometimes less—all depending on the weather situation and humidity in the air.

Millions of wafers

The wafer bakery in Bielefeld produces wafers about ten hours a day—four days a week. Three full-time and several part-time workers ensure a smooth production process. At least two employees have to be there in order to keep production running.

Every two weeks, the bakery takes delivery of around four tons of flour. This suffices for eight to ten workdays. Some 95 million wafers are produced each year. These are distributed to more than 60,000 congregations around the world. But these wafers are not the only things that are baked in Bielefeld. But that is a different story …