Drops, applicators, technology: how the wine got on the wafer

Once things were official, the problems started in earnest: how will the wine get on the wafers? It was a long road from handmade applicators and waffle irons to today’s fully automated production facilities.

Bread and wine in one—for one hundred years this has been the standard practice for Holy Communion in the New Apostolic Church. How this came about? In World War One it was almost impossible to find wine. In addition, there was a fear of epidemics. The faithful were still sipping from the communion cup. The most hygienic and efficient solution: wafers with three drops of wine, as they were already being sent to soldiers at the front. Chief Apostle Hermann Niehaus introduced this new practice starting Good Friday 1917. It became binding for the whole Church in 1919.

Where do we get bread and wine from for Holy Communion? There was know-how and something akin to a Church-owned marketplace in Germany at the time: the adverts run in the official Church magazine of the day. A man by the name of Carl Ehrler from Plauen, for example, offered an excellent red wine for all the rectors. And Ewald Dissel from Ruhrort advertised communion cups and wafers besides cigars and stationery.

Applying the wine

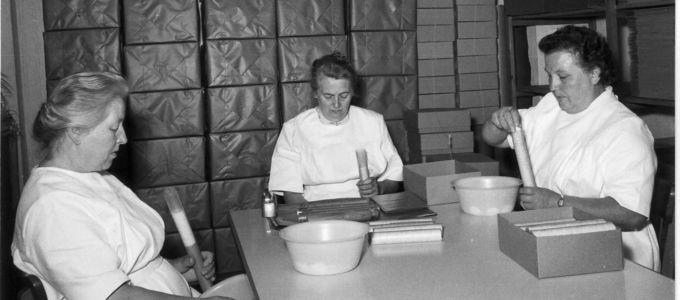

What was quite challenging was getting the three drops of wine on to a sufficient quantity of wafers. Elderly members today still remember how they would sit around the table with their families as children and, using an eyedropper, apply wine to hundreds of wafers—enough to supply a congregation of several hundred members.

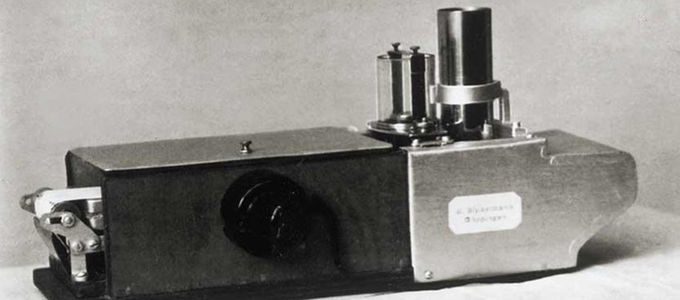

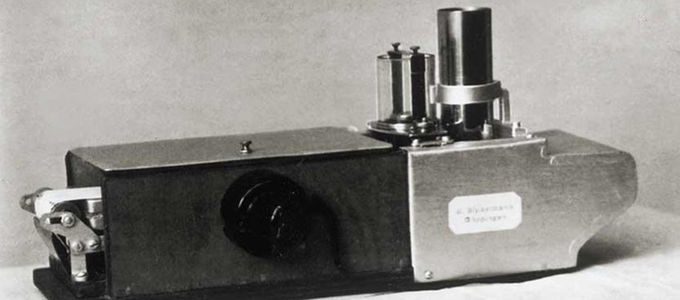

Things became a little easier with a stippler, a kind of stamping device that was constructed by a member of the Church in Göppingen. “It is best if you buy a small bottle of good red wine and then brush it on several thousand wafers,” Apostle Johann Gottfried Bischoff recommended to the ministers in a letter. “It is best to put the wafers on a clean while cloth or a piece of blotting paper. If you use other materials, the wafers may stick to it,” he suggested.

From secretary to boss

Things began to be more professional when Max Pflug, a master baker and a Priest in the congregation in Herne (Germany), started with the production of communion wafers. The batter was still made by hand and baked in a kind of oversized waffle iron. In 1931 the Church took over his company and the Chief Apostle’s secretary, Helene Herterich, was put in command. At the new headquarters in Bielefeld, the first Church-owned communion bakery was established. It still exists today. The first domestic delivery went to the Rhineland, the first international one to Australia.

World War Two brought new problems. Wine and flour could only be bought with a ration coupon. And for this, Helene Herterich had to go to Unna and speak to the responsible authorities: left the house at six o‘clock in the morning; four hour train journey; trouble with the authorities because coupons had supposedly been sent; the train home at nine in the evening was overcrowded; waited for freight train at eleven o’clock (standing room only). “I arrived home at eight o’clock the next morning,” she wrote. “What strain!”

Bielefeld supplies the world

The Church grew and so did the communion bakery: from a yearly production of 9.7 million at the beginning to 238 million in the year 2001. A milestone was the first automatic bread line in 1979, an in-house design monitored by engineers. Even though the manufacturing machine was twice as fast as originally planned, by 1990 a more powerful one was needed.

In order to keep costs low, additional communion bakeries were opened in Cape Town (South Africa) in 2003 and in Lusaka (Zambia) in 2012—the two largest consumers of wafers. The work was supervised by the professionals from Bielefeld (Germany). While the production in Africa is semi-automatic, the small bakery in India produces wafers by hand. The same was the case in Hong Kong two years ago, where a stippler was put through its paces.

“Very interesting technology getting these three drops on the wafers,” was how South-East Asia summed things up. The production process can be tricky. But that is another story and will be told another time.