When a mission becomes a brand and faith becomes a success story, you lose sight of the cross. But Jesus reminds us in an unnerving kind of way that love is not measured by how many people have been exposed to it, but by true discipleship.

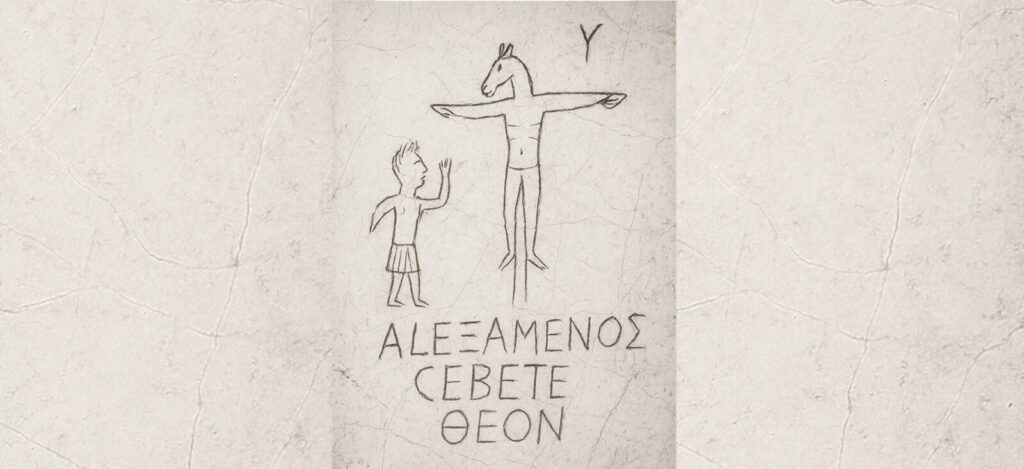

The earliest known depiction of the crucifixion of Christ is not a church treasure but sheer mockery. A graffito scratched into a wall of a boarding house for imperial page boys was discovered on the Palatine Hill in the heart of Rome (dated late second to early third century). It depicts a crucified donkey-headed figure. Next to it is a person praying and a Greek inscription that roughly reads “Alexamenos worships [his] god”, meant as an insult.

Illustration of the so-called Alexamenos graffito.

“We preach Christ crucified … a stumbling block and … foolishness”

(1 Corinthians 1: 23).

All along: a narrow path

Forty days after Jesus’ birth, Mary and Joseph carried the infant into the temple. Simeon, an old prophet, took the baby in his arms, sang of the light that would be brought to the nations, and quietly prophesied that the child would be a sign that will be spoken against (Luke 2: 34).

Jesus Himself never shied away from unpleasant or difficult subjects. He preached the cross instead of comfort (Mark 8: 34), including mockery (Matthew 5: 11–12; Luke 6: 22–23), and said that headwinds were to be expected. “If the world hates you, you know that it hated Me before it hated you” (John 15: 18–20).

The often-used image of taking up one’s cross is initially not pious, but brutal. When Jesus said that a person must take up his cross and follow Him (Mark 8: 34; Luke 9: 23; Luke 14: 27), He meant the path of a condemned person to execution—shame and powerlessness. The cross does not stand for every personal difficulty, but for the suffering caused by following Jesus, namely for Jesus’ sake. Those who follow Christ are therefore prepared to accept loss. And they are prepared to give up their own ego and to give priority to God’s will, in other words, are prepared to deny themselves.

When a mission becomes a brand

Following Christ is often sold as a kind of wellness package. Faith is made into a problem solver. The prosperity gospel, or theology of success, works with a subtle logic of entitlement: proper belief + positive profession of faith + generous giving = health, money, and success.

But this would be Easter without Good Friday, the resurrection without death, and triumph without faithfulness. And because Christian churches are struggling against a decline in church attendance, it is easy to fall into similar tendencies with good intentions: missionary zeal becomes brand logic. It sounds like this: “The Church must become attractive.”

Through changed language, believers are led to believe that they can activate blessings. The stage is set so that the growth curve moves in the right direction. Those who suffer quickly feel inadequate—so everything is made to look good.

The only thing is, Jesus never sold accessories. Initially, the cross is not a pendant, but a cause. It rubs one the wrong way, is disturbing, and turns priorities upside down: unconditional love instead of a self-centred attitude, truthfulness instead of convenience, devotion instead of self-optimisation. The standard is not reach, but love.

When following Christ is a disadvantage

Jesus does not seek controversy for the sake of controversy. In Luke 12: 51–53, He exposes false peace: the comfortable calm that covers up existential questions. His peace is different: “Peace I leave with you, My peace I give to you” (John 14: 27). He brings truth, and truth separates us from self-deception. It is both uncomfortable because it exposes us and healing because it reconciles.

Suffering as a Christian—the “cross”—does not mean self-destruction, but faithfulness in the face of adversity. Suffering is not sought, but accepted when faith, truth, and mercy are at stake. Not all suffering is suffering for the sake of discipleship. We are not talking about personal hardship, but suffering for the sake of Jesus, for example, when truthfulness has drawbacks or mercy goes against the tide. Discipleship comes at a price because it does not follow the logic of self-preservation but the logic of love.

Not the end of the line, but a path

“I am the door. If anyone enters by Me, he will be saved” (John 10: 9). Suffering for the sake of Christ is not an end in itself, but a path as described in the following: “We must through many tribulations enter the kingdom of God” (Acts 14: 22): “Ought not the Christ to have suffered these things and to enter into His glory?” (Luke 24: 26).

When Jesus says that whoever loses their life for His sake will find it, He is not talking about a literal desire for death, but about letting go, namely relinquishing control. Specifically, this means forgiving instead of insisting on being right, speaking truthfully despite disadvantages, sharing and serving instead of just consuming, following our inner moral compass, following our conscience, and supporting the weak. In this way, the cross leads through a narrow passage to a wider, more profound life in Christ. And those who walk this path discover greater freedom. They are free to live the truth of the gospel without fear of losing face (1 Peter 4: 12–16), they are free from fear (Hebrews 2: 14–15), and free to love (Galatians 5: 13).

Photo: AI-generated