Did the New Apostolic Deaconesses of the early decades carry a spiritual ministry or not? Before we can answer this we have to clear up two further questions. First, were the women ordained? And secondly, what were their duties? Here is the current state of research.

In the first eighty years of the New Apostolic tradition, Deaconesses were anything but rare. Deaconesses are documented for Europe, America, and Africa and, depending on the region, sometimes represented one sixth of the Church’s official ministers.

The New Apostolic congregations had inherited Deaconesses from the Catholic Apostolic Church. There they were not allowed to exercise liturgical functions in divine service. And Deaconesses did not receive a blessing from an Apostle, but one from the congregational Bishop. However, this was about to change in the New Apostolic Church.

At the service of women

At first, nothing changed. Our first proper liturgy from 1864 bears witness to this: “The Deaconesses do not exercise an independent ministry, but assist the ministers there where female service and care is required.”

Something similar can be found in the Hülfsbuch, the first textbook published in 1908 for Priests and teachers: “Deaconesses are to be appointed as required to support the Deacon and Sub-deacon ministries. Deaconesses are installed by special mandate of the rector. They are to serve especially among single women or widows, also sick women, where no man may go.”

Acting as proxies at the altar

In practice, Deaconesses had long since taken over certain duties in divine service: “Therefore the holders of the ministry, the oldest Deacon present and the oldest Deaconess present are appointed,” to receive Holy Communion for the departed. This was the uniform rule announced by Chief Apostle Friedrich Krebs in 1898.

It is likely that Deaconesses also served as substitutes for baptism with water and Holy Sealing. Because in 1910 the Apostles’ College had decided “exactly the same procedure should be followed for the sealing of the departed as for Holy Communion for the departed”.

In some cases, Deaconesses also helped to dispense Holy Communion. This was reported by the later Chief Apostle Johann Gottfried Bischoff in 1929 in a publication for ministers entitled Leitstern (“Guiding star”). “During the war, for example, there were so few ministers and brothers in some congregations that Deaconesses were needed to dispense Holy Communion.”

With the blessing of the Apostle

Early sources reveal little about the actual appointment of Deaconesses. The oldest known report at present is from 1874 and mentions that in the congregation of Enkhuizen “Brother S. Sterk and Sister Sterk-Bezaan were blessed as Deacon and Deaconess”. Man and woman were thus treated equally.

A report on appointments in the Hamburg congregation is noteworthy: three women “to whom the ministry of Deaconess had already been entrusted” received “the apostolic blessing” in December 1897. Unlike in the Catholic Apostolic Church, Deaconesses received their ministry in the same way as male ministers..

Ordained into ministry

So were Deaconesses ordained? In their heyday, the term “ordination” had fallen out of use in German. Originating in the Netherlands, which was influenced by Calvinism, the word had been supplanted by “institution” and only made a comeback in the 1970s. In English, meanwhile, the term “ordained” continued to be used.

The New Apostolic church historian Manfred Henke, who has a doctorate in history, took a close look at the matter: “Based on a study of word usage, I conclude that Deaconesses were ordained in the New Apostolic Church.”

More for than against

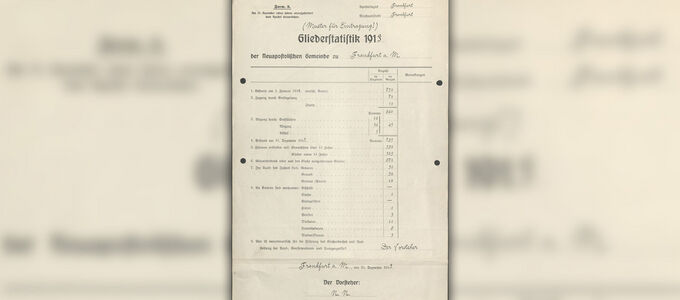

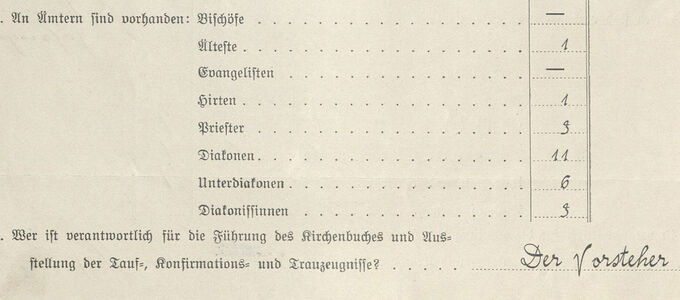

There are other indications that Deaconesses were regarded as ministers. In 1919, for example, there were 24 Sub-deaconesses in addition to 19 Deaconesses in the Netherlands. In his ordination statistics, which he kept from 1930 to 1951, Assistant Chief Apostle Heinrich Franz Schlaphoff listed Deaconesses between Sub-deacons and Deacons.

Deaconesses as ordained ministers clearly shows that the history of the New Apostolic Church speaks more for than against women in ministry. However, there is no fundamental doctrinal justification for the practice in the first eighty years as well as in the second eight decades.

This article is based on as yet unpublished preliminary material by the church historian Manfred Henke, who is compiling a scholarly work on the history of the New Apostolic Church.