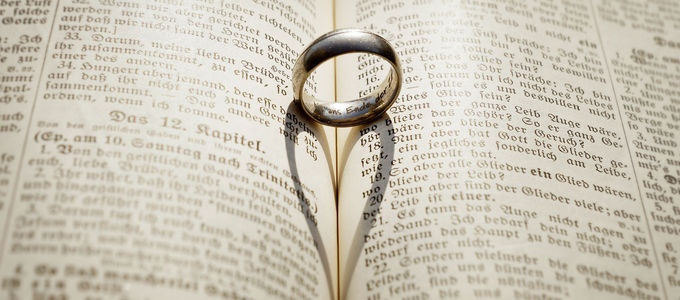

God, man, and love

“Our God is loving.” Who of us did not sing this song as a child? It is a short, catchy, and simple statement. Yet at the same time it is momentous, difficult to grasp, and confusing to understand. “We praise Him evermore. Our God is loving.” What does this mean?

God creates man in His image and gives him the space he needs to live and unfold and shape his existence in the creation. As a consequence of their fall into sin, human beings had to leave the fellowship they shared with God in Paradise. But God’s love appears in man’s fall into sin: He promises a Saviour (Genesis 3: 7 et seq.).

Love by contract

In the Old Testament, God’s love is primarily revealed as love for His people. It is a free, choosing kind of love. No one is entitled to it. God did not care for and choose the Israelites because there were many of them—they were the smallest nation of all—but because He loved them (Deuteronomy 7: 7–8). In order to express that which is incomprehensible, the biblical scriptures use comparisons: God loves Israel as a man loves His wife, as a father loves his son (Hosea 2: 18; 11: 1, Deuteronomy 14: 1; 32: 6), and as a mother loves her children (Isaiah 49: 15; 66: 13).

In return, Israel is given the command to love God. You shall the Lord your God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your strength (Deuteronomy 6: 4–5). Israel has entered a covenant with God. The Hebrew b’rit (its English meaning is covenant, pact, or treaty) is a legal term. The command to love God is a political directive to keep the covenant and not commit a breach of contract.

Love for the commandments

The Israelites’ love for God becomes concrete in the keeping of God’s commandments (Deuteronomy 10: 12 et seq.), because the Mosaic Law is the object of the contract between God and Israel. God, in turn, is faithful to those who love Him and keep His commandments. He preserves (Judges 5: 31; Psalm 31: 23; 145: 20), delivers (Psalm 91: 14), and shows mercy to those who love Him (Exodus 20: 6). Love that is not reciprocated will withdraw.

Although the commandments are an obligation, they certainly are also an expression of God’s love because they afford those who keep them a life in freedom. One of the answers to God’s love is love of one’s neighbour. It was the love of one’s neighbour that initially determined the relationship of the Israelites among each other (Leviticus 19: 18), but it was also to be shared with the stranger (Exodus 23: 9).

Where there is love, there is jealousy

The legal understanding of love quickly led to the metaphor of a marriage between God and His people. The book of Hosea puts this in words drastic words. The prophet accuses the people of unfaithfulness, adultery, and whoredom (Hosea 1). This prophetical book describes God’s jealousy and His fierce anger over Israel’s apostasy (Hosea 11: 9 et seq.).

Using the metaphor of love, Hosea describes the exclusive and intense love of God for His chosen people, which is always greater than His wrath: despite their disloyalty, God does not reject Israel, but promises them salvation and assures them His love and faithfulness (Hosea 14: 5).

Jesus Christ, the love of God

The incarnation of God’s Son gave rise to the subsequent crucial development. In the old covenant, God revealed Himself exclusively in His love for the people of Israel. In the new covenant, however, it is Jesus Christ Himself who is the revelation of God’s love for mankind (John 3: 16).

God is no longer distant and invisible, but whoever has seen Jesus has seen God (John 14: 9). Jesus’ life—His concern for the poor, the weak, the rejected, and sinners—is a concrete image for the love of God. In Jesus Christ the love of God becomes tangible.

The greatest commandment

Jesus does not abolish the Old Testament conception of love between God and His people, but refers to it very explicitly: He declares that love for God is the greatest commandment. Jesus likens it (Matthew 22: 39) to the commandment to love one’s neighbour (Leviticus 19: 18), which is why they are also referred to as the double commandment of love. With this reference to the Torah Jesus confirms the Jewish tradition. He understands Himself as having been sent to the Jews.

However, He also performs healings and miracles on non-Jews (Matthew 8: 5 et seq; 19: 21 et seq.). His deeds are therefore already an indication of His love extending beyond the Jewish people. In the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10: 25–37), Jesus extends the term neighbour. In the Sermon on the Mount, and as a special form of neighbourly love, He exhorts the listeners to love their enemies (Matthew 5: 43–48).

Eternal love

The love of God in Christ culminates in the message of the cross: out of love God places Himself on the same level as man. He lives, loves, suffers, and dies a human death on the cross. Instead of the exclusive love of God for His people, the focus now is on the sacrificial love for mankind—regardless of their ethnicity.

Because of the sacrifice of Christ, Paul sees God’s love for mankind as an eternal, inseparable relationship. Nothing will be able to separate man from the love of God (Romans 8: 38–39). It is a gift of God, which mankind can only answer with love. Paul considers this the highest Christian virtue, which he praises and describes in his song of divine love in 1 Corinthians 13.

The New Testament appeals concerning love are an exhortation to act as God did as much as possible. Man must do his utmost to love. 1 John 4 literally develops a theology of love, God Himself is identified with love: God is love; and whoever abides in love abides in God, and God in him (1 John 4: 16).

Photo: underdogstudios - stock.adobe.com