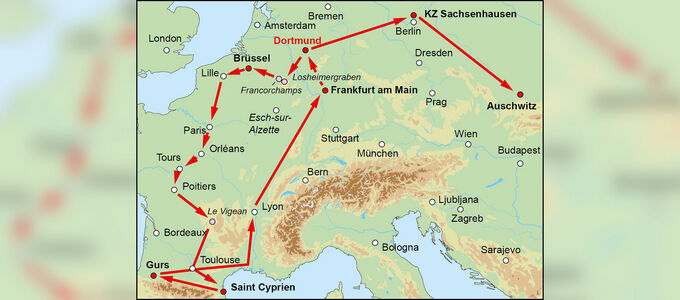

The long road to Auschwitz

At first, Harry Fränkel sought refuge in South Africa then in America. His last years, however, took him via Belgium and France to his death. We pay tribute to his memory as the world marks International Holocaust Remembrance Day today, January 27.

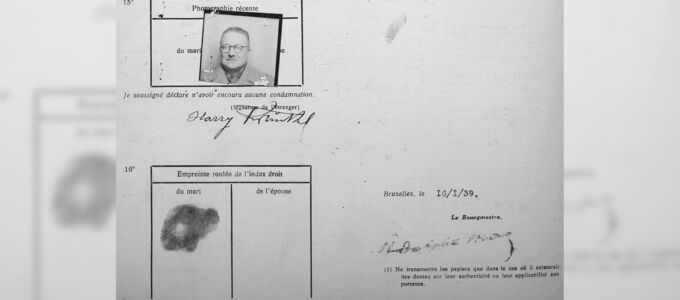

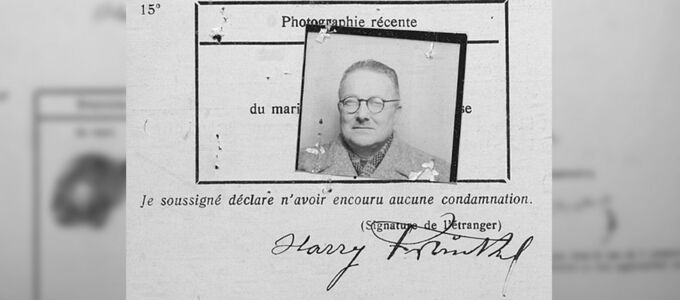

The 11th of January 1939 was a mild winter day in the Eifel region in Germany. Ideal conditions for a 30-kilometre walk from Germany to Belgium. Harry Fränkel was fleeing persecution and arrest. This is what the man, a Jew by birth, stated when he was questioned in Brussels, Belgium.

The people questioning him also wanted to know whether he had any income. Yes, Harry Fränkel replied and told them that he received 400 francs a month from a certain Lucien Bouquet, a pastor from Luxembourg. Bouquet is the rector of the New Apostolic congregation Esch-sur-Alzette. Apparently, Fränkel was receiving financial support through him from the Apostle district of Switzerland.

Father, Priest, entrepreneur

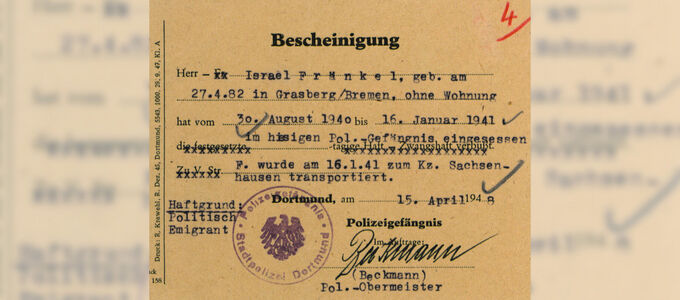

Harry Fränkel was born on 27 April 1882 near Bremen in northern Germany. His parents, Salomon and Eliese Fränkel were Jewish. He converted and became New Apostolic on 23 July 1908. In 1909 already he was a Sunday School teacher in Dortmund. In 1911 he was ordained as a Deacon and then, around 1922, as a Priest.

He was a successful textile merchant. He could afford to send his three children to college. And the family could afford domestic help. And then the year 1933 dawned—the year in which the Nazis seized power in Germany.

Under persecution

Fränkel, a so-called full Jew because both parents were Jews, lost his job as managing director of the company Mayer & Günther. He started his own business. Advertisements in the German-language magazine Unsere Familie, for example, document this. In 1938, however, legislation forbade him from running his own business. His son Erich took over. Before long, he too was forbidden from carrying on with the business.

Meanwhile, Priest Fränkel was asked to suspend his ministerial activity—to protect the Church. Reprints of the choir folder omitted his name as a hymn writer. His son Harry Jr., a graphic designer and illustrator, was refused admission to the academy of arts. It was becoming harder and hard to find work for him. This is when Fränkel Sr. decided to emigrate.

On the run

A first attempt was to take him to South Africa. Harry Fränkel wrote to Assistant Chief Apostle Heinrich Franz Schlaphoff, but he was unable to help. By decree, South Africa closed itself off to European Jews. The Apostle, however, gave him the address of a contact in Argentina.

Belgium was the gateway to the free world at the time. The country was more liberal in terms of refugees than its European neighbours. For 17 months, Harry Fränkel lived in Brussels in five different locations—separated from his family, friends, and congregation. While he fought for permission to be able to stay in Brussels, the Gestapo, the secret police of the Nazi regime, knew of his whereabouts. And then came 10 May 1940, the day Germany invaded Belgium.

Deported and interned

Some 10,000 men were arrested in Belgium on that day because they were suddenly labelled as enemy foreigners and were considered a threat for the country. In a mass deportation they were carted off to France by rail. There was hardly anything to drink in the overheated and overcrowded wagons, nothing to sit on or lie down on, no toilets…

This brought Harry Fränkel close to the French-Spanish border. First, he was taken to the Saint-Cyprien camp, Block 1, Barrack No I 42, and then to a placed called Gurs, which was considered the most horrifying concentration camp in France. And that meant: hunger, cold, vermin, disease, and death. And then came the day when France surrendered to Germany, 22 June 1940.

In hell

The armistice was followed by an extradition treaty. Harry Fränkel set out on his final journey. It took him via pre-trial confinement in Frankfurt (Germany) and the notorious Steinwache (a prison used by the Gestapo) in Dortmund—barely two kilometres away from his home and family—to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin and finally to Auschwitz.

His life ended in this hell-hole on 5 November 1942 at 8 a.m.: “murdered” as the International Holocaust Remembrance Center Yad Vashem puts it. However, his name lives on, as the writer of a New Apostolic hymn “Take off your shoes, for the place where you stand is holy”.

A more detailed account of Harry Fränkel’s fate can be found in the book Inszenierte Loyalitäten – Die Neuapostolische Kirche in der NS-Zeit by Dr Karl-Peter Krauss, a historian. Chapter 10.3 of the book is based on preliminary work by Professor Günter Törner.